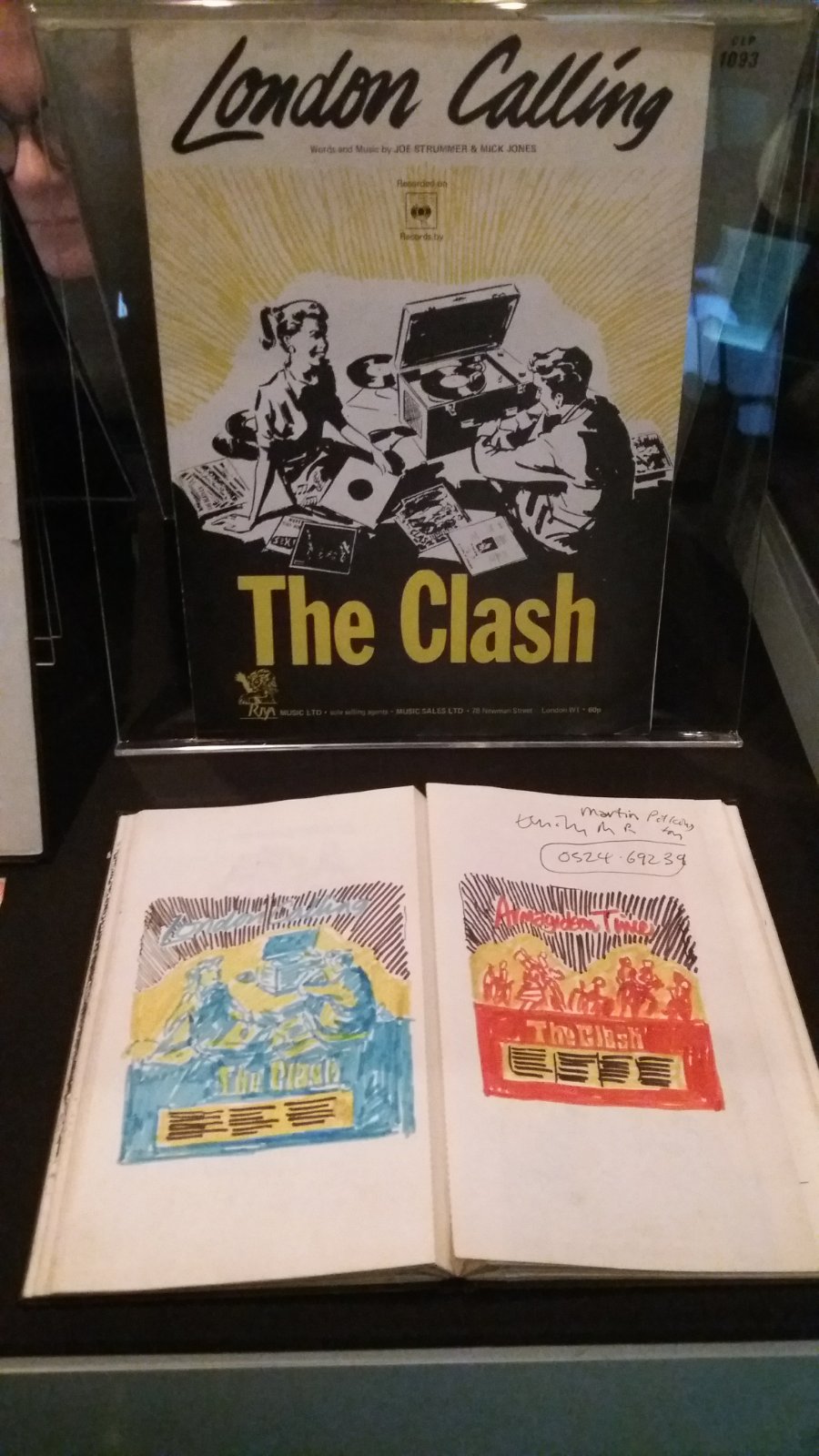

Persistent rumors of “lost” Clash recordings haunted die-hard fans for a solid 25 years. According to legend, The Clash documented London Calling rehearsals in a makeshift practice room at Vanilla Studios. This coveted material failed to surface, leading many to question whether the “Vanilla Tapes” actually existed.

The “London Calling” lyrics reflect the chaos that was engulfing the world at the time. Much of London Calling was crafted while the Clash traveled across the globe in 1979. It was a period. 'London Calling' by The Clash is a truly iconic song, so much so that it crashes into the 15th spot on Rolling Stones' list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. Besides 'Should I Stay or Should I Go,' it is the Clash song. The Clash, the doom of the early eighties perfectly. Fortunately, the group that is not on a dismal manner. Songs like Spanish Bombs and Lost In The supermarket, despite the serious texts, spirited songs who mercilessly between the ears. Despite the span of an hour, there is not a bad song on London Calling.

Joe Strummer first hinted at the existence of self-made tapes during a 1979 interview. Strummer proposed that bands could avoid expensive studio bills by recording on simple Teac machines. It was a noble idea, perhaps a way to extricate The Clash from corporate control. Strummer’s bluff must have shaken up record execs. Despite being a double album, London Calling was released with the street price of a single LP.

Verification of the Vanilla Tapes finally came in 1997 when Clash roadie, Johnny Green published “A Riot of Our Own: Night and Day with the Clash.” Among recollections of road-life, Green provided a detailed account of the sessions in question.

When The Clash severed ties with their manager in 1978, they lost access to their rehearsal building. Necessity brought the band to Vanilla Studios. This was no professional music space, but an old factory refurbished as an auto-repair shop. The benefit of using the unorthodox space was total isolation from the punk scene. Without the distraction of hangers-on, The Clash focused their energies on music. In the summer of 1979, the songs that comprise London Calling organically came together amidst broken cars and exhaust fumes.

Inside their new home, the band installed a 4-track tape machine. Practices were recorded and cassettes made for band members. Each musician could monitor progress and reflect on their individual contributions.

The story would have ended there if not for Mick Jones. In 2004, the guitarist was preparing to move into a new residence when he discovered the The Vanilla Tapes inside a forgotten cardboard box!

Oddly enough, the discovery coincided with the 25th anniversary of London Calling. Columbia Records released a deluxe edition of the landmark album with the Vanilla Tapes included as a bonus disc. Although the three disc set is long out of print, used copies are still available online.

Exploring the Vanilla Tapes offers a unique insight into a band pushing the boundaries of punk rock. The songs exist in various degrees of completion. Fragments of undeveloped ideas coexist beside completed songs. Some tracks are performed as instrumentals while others have distinctively different lyrics. There are four original songs that never made London Calling, a rehashing of “Complete Control,” and even a Bob Dylan cover.

The bonus disc kicks off with an instrumental version of “Hateful.” Musically complex with a rabid guitar solo, the basic structure is in tact. Hearing the Clash in a raw, stripped-down form is intensely satisfying.

“Rudie Can’t Fail” is the sound of The Clash in the experimental stage. Most of the structure and lyrics are complete, yet the band actively explores ideas. When the phrase “YOU’VE BEEN A NAUGHTY BOY” comes distinctly from the right speaker, it’s uttered with a hint of repressed laughter. The band is having genuine fun. It’s a shame the line, “Brew…DRAGON BREW” never made the final version!

The Clash London Calling

“Paul’s Tune” is an early version of “The Guns of Brixton.” Built around Paul Simonon’s bass line, it exists here as a quick stumble through the basic melody. Considering that The Vanilla Tapes were made just weeks before recording London Calling, the incomplete “Paul’s Tune” reveals just how quickly The Clash were writing songs during this period.

In those feverish final weeks before entering Wessex studios, The Clash worked to refine their new batch of songs. The Vanilla version of “I’m Not Down” shines light on how the band continued to revise lyrics until they were satisfied.

“Koka Kola, Advertising & Cocaine” is a song that is ALMOST done but not quite. Just as the title would be modified for the album, each verse falls victim to revision. Musically, the bridge is present. Joe Strummer simply ad-libs phrases in the absence of lyrics.

“The Police Walked in 4 Jazz,” is a prime example of what makes the Vanilla Tapes special. Acoustic and electric guitars mingle together. Judging from the title, a basic concept was in place, even if the lyrics had not yet been written. Performed as an instrumental, it’s interesting to hear lead guitar play the vocal melody.

About two minutes in, the band grows impatient. Topper’s drumming pushes the song into a new direction and the electric guitar obliges by falling into an offbeat rhythm that goes nowhere. The tape cuts off; leaving a glimpse into an incomplete idea that was destined to become a Clash classic.

Other songs exist in this manner. Just weeks before recording London Calling, “The Right Profile” was merely an instrumental. Judging from the title “Up-Toon,” ideas for lyrical content were non-existent at this stage.

The Clash continued to tweak songs until the last minute. This constant evolution is most notable in the title track to London Calling. The anthem would undergo a dramatic rewrite. In the original version presented on the Vanilla Tapes, most of the lyrics are unrecognizable.

With so many stories of “lost” recordings littering the rock and roll landscape, it’s nice to have a priceless artifact materialize. While the Vanilla Tapes currently remains out of print, the digital era of the Internet age ensures that this classic material will never elude Clash fans again.

While the word has metastasized into a cliche, 'London Calling' by The Clash is a truly iconic song, so much so that it crashes into the 15th spot on Rolling Stones' list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. Besides 'Should I Stay or Should I Go,' it is the Clash song. It appears in the James Bond film Die Another Day and in countdown coverage for the 2012 Olympics.

But, as Alan Connor quotes Marcus Gray in a piece for the BBC 'London Calling is a classic example of a song that has become so familiar that its original meaning has been lost. It's instantly recognisable and superficially the perfect invitation to the capital and the world's premiere sporting event, but it's actually about the end of the world, at least as we know it.'

Yes, the opening chords are almost instantly recognizable. Yes, it's got the word 'London' in it. But surely, no matter how cool it is, it's not the best song to use for a London tagline, is it? That's the question Alan Connor asks in his article 'Smashed Hits: Is London Calling the best anthem for a city?'

His main point begins with the song's title and recurring lyric: 'London Calling.' 'London Calling' comes from the World War II introduction for BBC radio broadcasts to foreign countries: 'This is London Calling. The news from Britain – up-to-the-minute, truthful.' The Clash have war on their minds.

Phony Beatlemania

When you listen to what the words are directly stating, the apocalyptic doesn't so much creep as snarl throughout every verse and every chorus. When he explained to the Wall Street Journal the meaning of one of the most memorable lines — 'Phony Beatlemania has bitten the dust' — Mick Jones rebuked the rationale behind using 'London Calling' as the city's anthem: 'The line about phony Beatlemania biting the dust was aimed at all the touristy sound-alike rock bands in London in the late '70s. We were fans of The Beatles, The Who and The Kinks—but we wanted to remake all of that... Our message was more urgent—that things were going to pieces.' This follows directly from a command for the fans 'don't look to us.' The Three Mile Island nuclear reactor had melted down earlier that year, threats of the Thames overflowing and flooding London were rampant, and the newspapers were heralding plagues every day. The feeling of the scene was just as heavy with doomsday as today.

The Clash London Calling Rare

In the midst of the apocalypse, the song cackles in gallows humor. The chorus builds up, layering nuclear era upon sun drawing near upon wheat growing thin until Joe Strummer breaks it off to say he doesn't fear any of that. Why? Because London is drowning and he lives by the river, making him the first to go. The song is directed to the boys, girls, and zombies all around, telling them to wake up to the catastrophes occurring all around them.

Which London is Joe Strummer calling?

A few days after Alan Connor's article was published, Scott Simon, host of Weekend Edition, sat with him to talk about the disconnect. The song 'London Calling,' like many of the other songs by The Clash, revel in a left-wing political perspective. '[The song's] celebrating London,' Connor explains, 'but it's also repudiating the previous decade's idea of London. When he says, 'We ain't got no swing,' I think Joe Strummer is trying to put in the bin the red-bus, black-taxi, groovy-baby kind of London.' More than that, however, is that the only swing left in London is the ring of a truncheon.

The Clash London Calling Meaning

The sixties and all the touristic Disneyfication of London had to be ripped away so that the people the song addresses, whom the song shouts at for nodding out, can stand up for themselves. It's an excellent song and it rightfully earns its place as an iconic punk song, but using a song that rails against the papering over the troubles of the world as an ad for a fake London is not in the spirit of 'London Calling.'